Dad,

Really, you don’t seem to be holding very much space for the French musical about transing the Mexican drug lords, an issue of vital importance to all Americans. Don’t you know how many people on TikTok are finding solidarity with the lyrics of Emilia Pérez? It’s like you don’t even work in queer media.

But alas, yes. Many of this year’s Oscar’s movies—even the moderately diverting ones like Wicked—were vanity, all vanity. A weirdly appropriate thing to observe right now, since it’s the first week of Lent. On Wednesday, many Christians received the mark of the cross on their foreheads in ash with the solemn reminder from Genesis: “dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.” How’s that for vanity!

All week, you and I have been meditating on a single little bead of gray matter. From one perspective it’s a marvel of complexity, elaborately networked and dazzlingly baroque in its tiny structure. From another perspective, though, it’s just so much fancy gunk. The most beautiful physical object imaginable—and the brain is a good contender—will disintegrate into a heap of particles one day. The brain, without the mind, is so much dust.

You wrote that the whole thing reminded you of Hamlet’s line about being “bounded in a nutshell.” It reminded me of another speech from the same play, by the same character. “What a piece of work is man,” says Hamlet, invoking the psalms, marveling at the Renaissance vision of human form and power. “And yet, to me”—to Hamlet in the free-fall of his doubt, unsure of what lies beyond this mortal coil, flailing in an endless dark—“what is this quintessence of dust?”

Masterly Shakespearean wordplay, since the original meaning of “quintessence” was rarified spiritual matter, the elusive “fifth element” that was supposed to course like fire through the heavens to give them form and life. Humanity is a vessel for that divine flame—but the vessel is only dust.

So either the body, the brain, and the world are symbols, their structure giving visible form to invisible spirit, or they’re so much dirt. For centuries, our doubt-maddened intellectuals have adopted the latter view, as Hamlet knew they must.

And here’s the thing: if dust is all we are, then death is all we can expect. You can try to avoid this conclusion, and Lord knows we’ve tried. You can wrap your materialism in a Dior gown and walk it down the red carpet. You can say we’re made of star-stuff, like Carl Sagan did, and isn’t that wonderful, as Neil deGrasse Tyson agrees.

But it’s useless, all of it. Vanity, vanity: stardust is still just dust. A glamorous Netflix movie about a trans drug lord is still just a portrait of a criminal hacking at his own flesh.

In all its many forms, the revival we’ve been discussing is the first stirring of a recollection: like works of art, our bodies of ash and dust are either about more than just themselves, or they’re about nothing at all.

Love,

Spencer

Beautiful letter, Spencer. Since childhood I've held to the belief that after the body dies, the soul or spirit lives on...Whatever that means we will not know in this lifetime; it is a mystery, but somehow it relates to the personal lives we've lived, the people we love, and the goodness of God.

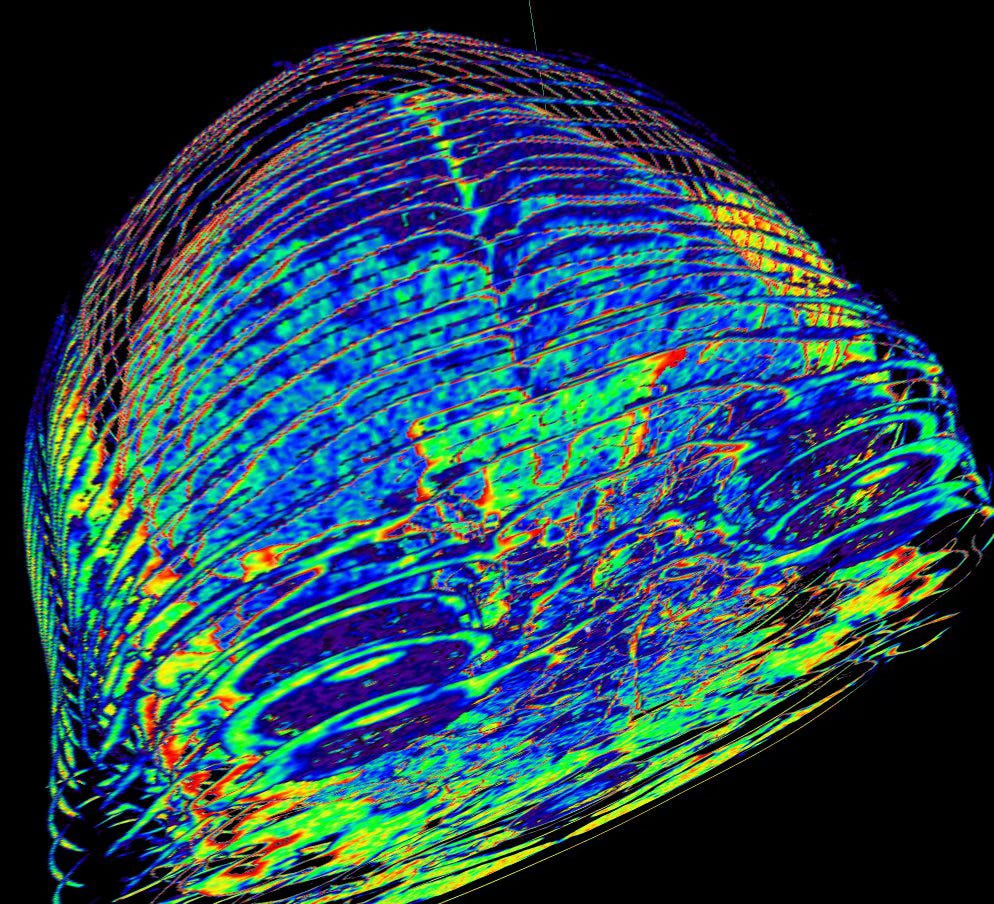

I have this image. Maybe from being present at the death of both of my parents. Maybe reading about near-death experiences. (My father had coded in the hospital before my sister and I could arrive. He was resuscitated. He kept telling us he wanted to go back to that beautiful White House on top of the hill.) Or maybe it was The Matrix. But I have felt recently that the brain is God’s way station where Divine energy connects to this material world. And the interaction of the material with God’s divine energy creates the mind. Once that plug is pulled, it’s all just gunk, as you note. But when it’s connected it is a grand beautiful dance to behold a universe within a universe.