Seeing the Supernatural

It's Right There Before Your Eyes

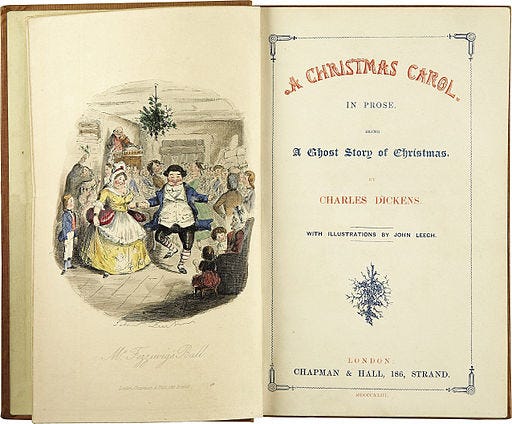

The last podcast I recorded in 2025 was a long meditation on Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. As I was writing out my thoughts in preparation for the show, a final observation came to me and I jotted it down. I thought it was a side issue, one of the many notes I would mentally discard as I was speaking. But when I came to it during the recording, I suddenly realized it was my central observation about the work.

Everything in A Christmas Carol depends on what Scrooge is and is not willing to see. All the spirits do in the story is show him things. Looking at those things changes him.

When Marley’s ghost approaches him, Scrooge uses materialist reasoning to talk himself out of believing what he sees. His senses are unreliable, he says. Indigestion might make them cheat. The ghost may be no more than “a fragment of an underdone potato.” Likewise, when the Spirit of Christmas Past confronts him with the anguishes and errors of his life, Scrooge wishes to extinguish the illuminating flame that rises from the Spirit’s head, to re-shroud the past in darkness.

Conversely, looking at what the Spirits show him teaches Scrooge a greater, more spiritual realism. Looking at Tiny Tim puts a human face on the suffering of poverty. Looking at his own headstone gives weight to the inevitable fact of death.

And so, through seeing, he is transformed. At the beginning of the story, Scrooge can explain away the sight of a ghost. At the end, he looks around at the ordinary objects of his home and sees the spiritual everywhere.

“There’s the saucepan that the gruel was in!” Scrooge cries out in wonder. “There’s the door, by which the Ghost of Jacob Marley entered! There’s the corner where the Ghost of Christmas Present sat! There’s the window where I saw the wandering Spirits! It’s all right, it’s all true, it all happened.”

This, to me, is key to understanding not just this work of fiction, but the nature of the supernatural. If you were to ask yourself: What would the world look like if there were an invisible God; if there were angels and demons warring for our souls; if there were miracles and ineffable realities that determine the eternal outcome of our lives?” the only sensible answer would be: It would look exactly like what we see right now. If those things are real, they are real this instant in the world as we know it.

Why, then, should we even care about spiritual life, you might ask, if it is no different than the life we already have?

But, in fact, seeing the reality of the supernatural changes everything.

Someone who looks on the material facts of life and convinces himself that any spiritual fact about them is nothing more than “a fragment of an underdone potato,” might find himself lost in implausible sophistries. He might, like Yuval Noah Harari, say something like this: “We never react to events in the outside world, but only to sensations in our own bodies. Nobody suffers because she lost her job, because she got divorced or because the government went to war. The only thing that makes people miserable is unpleasant sensations in their own bodies.”

Really? But what brought about those unpleasant physical sensations? Were they the cause or the effect of my sorrow? If I drugged away my feelings at having lost my job, would I no longer be miserable? Or would I merely be unable to feel my misery?

In a purely material world, everything is up to chance. Evolution is random. Even if the properties of matter determine its development over time, those determinations are themselves accidental and meaningless.

This, in paraphrase, is Richard Dawkins’ argument against the existence of God. But I cannot see the sense of it. If what we see as chance were, in fact, the design of a mind vastly larger and more complex than our own, how would we know?” Proof of such a design would be unavailable to our meager perceptions.

There would, however, be clues spread across our consciousness like breadcrumbs. For instance, one might notice that he was continually making moral assertions he in no way believed. “Nothing is good or bad but thinking makes it so. If everyone on earth approved of torturing children, then torturing children would be a moral good.” Or he might say, “I’m not sad because my spouse has died, I am only a flesh puppet made to feel what I call sadness because certain chemicals passed through my system when she died.” At this point, it might occur to one that, despite one’s high IQ, one was actually an idiot. If his worldview and his livelihood and his sense of himself as a smart person did not prevent it, he would then change his mind and begin to see.

What would he see and why would it matter? Well, for instance. I have watched more than one person destroyed by the obsessive hatreds that now seem to me to be devouring the soul of, say, Candace Owens. Their heads did not spin around. They did not walk on the ceiling. But to say that they merely experienced some shift in brain chemistry would be an obvious nonsense if the zeitgeist did not demand we perceive it so. To say instead that it is demonic possession is not to say that ugly little creatures with pitchforks rose from a fiery hell to invade the soul. It is simply to say that in a world shot through with consciousness, a person with free will was lured into self-destructive evil by a malevolent mind outside herself. Some force of will other than her own appealed to her desires and traumas and self-interests in order to convince her to open the door of her heart to its sinister influence.

Our treatment of a person in such a condition would be different than our treatment of someone experiencing a mechanical brain failure. It would not be the same as the medieval treatments of evil, any more than our treatment of tuberculosis would be the same as the treatments of the past. But it might offer pathways out of an essentially spiritual slavery that medications cannot offer.

In any case, if modernity has taught us anything it is this: to go blind to the spiritual is to lose track of the self. It stands to reason, then, that a happier, saner, more energetic life might await those who close their ears to the bright and brilliant nothings of pure reason, and open their eyes to what is at once invisible and yet standing right there before them.

What a wonderful essay for the new year! It’s so good to have you back! My own spiritual life is richer with the wisdom that you and Spencer bring to the table.

Andrew - , so great to read your wonderful column in the New Jerusalem this morning.

It is a profound truth. It reminded me a great deal about something that Dennis Prager wrote in this most outstanding Rationale Bible - the book on Exodus. Mr. Prager is writing about Moses and seeing the burning bush. Moses had a choice to see the truth of the burning bush or not to see it. This is such a critical point that you make in your essay and reiterated in a different way in Mr. Prager's writing. I have copied it below. Also, by the way, you said a wonderful similar thing in your book - The Great Good Thing. You said that after you came to faith, everything looked different and you saw God's hand and action in so many daily "miracles'.

the following quotation if from Dennis Prager's book - The Rationale Bible - Exodus.

“a sense, Moses’s behavior exemplifies a choice we all have when looking at life—am I seeing a miracle? Is the birth of a baby a miracle? Is thought, consciousness, great art—and, for that matter, all existence—a miracle? That is our choice to make. The Victorian-era British poet, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, commented on this verse: Earth’s crammed with heaven, And every common bush afire with God But only he who sees takes off his shoes. . . . 3 “Only he who sees . . .” That’s the great question: Who sees the miracles of daily life? And the answer is: Whoever chooses to see. One of the most important lessons of life—one I believe most people never learn—is that almost everything important is a choice. We choose whether to be happy (or, at the very least whether to act happy),”

Richard Hotchkiss